作为一所享誉全球的高校——哈佛大学,一直用“没有最低只有更低”的录取率(2018年秋季学期为4.59%)向大家彰显自己的地位。

想被录取,不仅要有超高的成绩、完美的简历、优秀的课外活动,文书也是影响成败的重要因素,在大家实力相当的时候,Essay是可以直接决定录取结果。

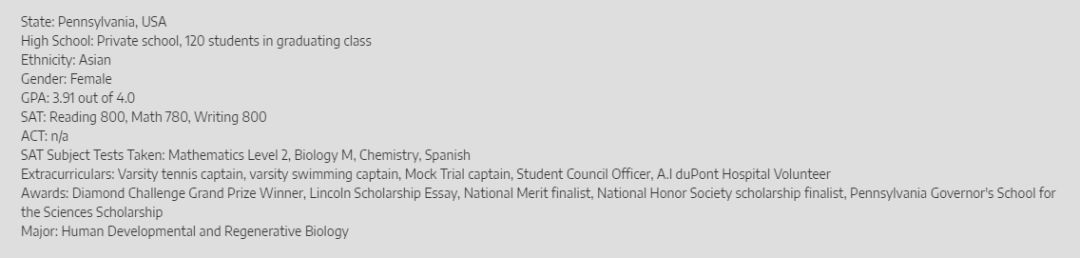

哈佛大学在官网上公布了10篇优秀Essay范文,来自2018年秋季入学的学霸们,还贴心的将学霸背景附上~贴出来5篇,我们一起找找差距~

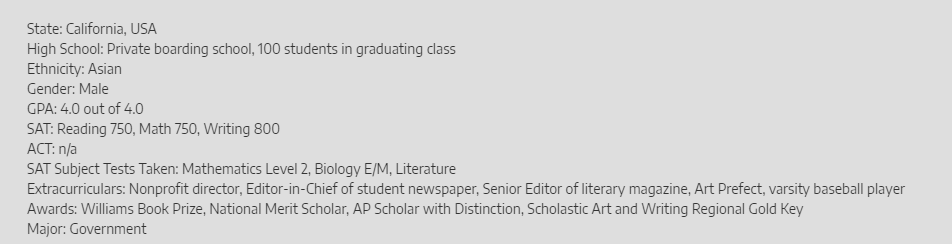

01

亚裔Bobby

ESSAY正文

Bold white rafters ran overhead, bearing upon their great iron shoulders the weight of the skylight above. Late evening rays streamed through these sprawling glass panes, casting a gentle glow upon all that they graced—paper and canvases and paintbrushes alike. As day became night, the soft luminescence of the art studio gave way to a fluorescent glare, defining the clean rectilinear lines of Dillon Art Center against the encroaching darkness. It was a studio like no other. Modern. Sophisticated. Professional.

And it was clean and white and nice.

But it just wasn’t it.

Because to me, there was only one “it,” and “it” was a little less than two thousand miles west, an unassuming little office building located amidst a cluster of similarly unassuming little office buildings, distinguishable from one another on the outside only by the rusted numbers nailed to each door. Inside, crude photocopies of students’ artwork plastered the once white walls. Those few openings in between the tapestry of art were dotted with grubby little handprints, repurposed by some overzealous young artist as another surface for creative expression. In the middle of the room lay two long tables, each covered with newspaper, upon which were scattered dried-up markers and lost erasers and bins of unwanted colored pencils. These were for the younger children. The older artists—myself included—sat around these tables with easels, in whatever space the limited confines of the studio allowed. The instructor sometimes talked, and we sometimes listened. Most of the time, though, it was just us—children, drawing and talking and laughing and sweating in the cluttered and overheated mess of an art studio.

No, it was not so clean and not so white and not so nice. But I have drawn—rather, lived—in this studio for most of my past ten years. I suppose this is strange, as the rest of my life can best be characterized by everything the studio is not: cleanliness and order and structure. But then again, the studio was like nothing else in my life, beyond anything in which I’ve ever felt comfortable or at ease.

Sure, I was frustrated at first. My carefully composed sketchbooks—the proportions just right, the contrast perfected, the whiteness of the background meticulously preserved—were often marred by the frenzied strokes of my instructor’s charcoal as he tried to teach me not to draw accurately, but passionately. I hated it. But thus was the fundamental gap in my artistic understanding—the difference between the surface realities that I wanted to depict, and the profound though elusive truths of the human condition that art could explore. It was the difference between drawing a man’s face and using abstraction to explore his soul.

And I can’t tell you exactly when or why my attitude changed, but eventually my own lines began to unabashedly disregard the rules of depth or tonality to which I had once dutifully adhered, my fervor leaving in its wake black fingerprints and smudges where once had existed unsoiled whiteness. It was in this studio that I eventually made the leap into a new realm of art—a realm in which I was neither experienced nor comfortable. Apart from surface manifestations altogether, this realm was simultaneously one of austere simplicity and aesthetic intricacy, of departure from realism and immersion in reality, of intense emotion and uninhibited expression. It was the realm of lines that could tell stories, of colors and figures that meant nothing and everything.

Indeed, it was the realm of disorder and messy studios and true art—a place where I could express the world like I saw it, in colors and strokes unrestrained by expectations or rules; a place where I could find refuge in the contours of my own chaotic lines; a place that was neither beautiful nor ideal, but real.

No, it was not so clean and not so white and not so nice.

But then again, neither is art.

点评:文章最突出的是意象组合,运用“Late evening rays …casting a gentle glow”,“the soft luminescence of the art studio…a fluorescent glare”将读者迅速带入作品,立马领会文章主题:艺术。这篇文章最吸引人的地方在于它是一个成长的故事,记录了Bobby从孩童到青少年的成长,艺术创作也从有序、浅显走向抽象、深刻。

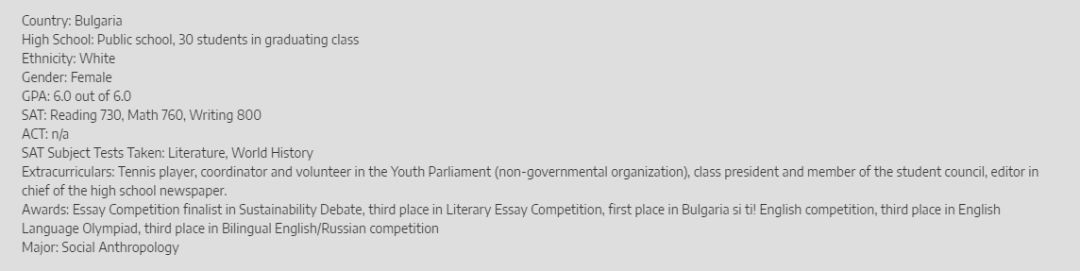

02

保加利亚的Jessica

ESSAY正文

As a child raised on two continents, my life has been defined by the “What if…?” question. What if I had actually been born in the United States? What if my parents had not won that Green card? What if we had stayed in the USA and had not come back to Bulgaria? These are the questions whose answers I will never know (unless, of course, they invent a time machine by 2050).

“Born in Bulgaria, lived in California, currently lives in Bulgaria” is what I always write in the About Me section of an Internet profile. Hidden behind that short statement is my journey of discovering where I belong.

My parents moved to the United States when I was two years old. For the next four years it was my home country. I was an American. I fell in love with Dr. Seuss books and the PBS Kids TV channel, Twizzlers and pepperoni, Halloweens and Thanksgivings the yellow school bus and the “Good job!” stickers.

It took just one day for all of that to disappear. When my mother said “We are moving back to Bulgaria,” I naively asked, “Is that a town or a state?”

Twenty hours later I was standing in the middle of an empty room, which itself was in the middle of an unknown country.

It was then that the “what if” — my newly imagined adversary—made its first appearance. It began to follow me on my way to school. It sat right behind me in class. No matter what I was doing, I could sense its ubiquitous presence.

The “what if” slowly took its time over the years. Just when it seemed to have faded away, it reappeared resuming its tormenting influence on me—a constant reminder of all that could have been. What if I had won that national competition in the United States? What if I joined a Florida tennis club? What if I became a part of an American non-governmental organization? Would I value my achievements more if I had continued riding that yellow school bus every morning?

But something—at first unforeseen and vastly unappreciated—gradually worked its way into my heart and mind loosening the tight grip of the “what if”—Bulgaria. I rediscovered my home country—hours spent in the library reading about Bulgaria’s history spreading over fourteen centuries, days reading books and comparing the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts, years traveling to some of the most remote corners of my country. It was a cathartic experience and with it finally came the discovery and acceptance of who I am.

I no longer feel the need to decide where I belong. I am like a football fan that roots for both teams during the game. (If John Isner ever plays a tennis match against Grigor Dimitrov, I will definitely be like that fan.) Bulgaria and the USA are not mutually exclusive. Instead, they complement each other in me, whether it be through incorporating English words in my daily speech, eating my American pancakes with Bulgarian white brine cheese, or still having difficulty communicating through gestures (we Bulgarians are notoriously famous for shaking our heads side to side when we mean “yes” and nodding to mean “no).

As a child raised on two continents, my life will be defined by the “What…?” question. What have Bulgaria and the USA given me? What can I give them back? What does the future hold for me? This time, I will not need a time machine to find the answers I am seeking.

点评:美国 VS 保加利亚,学者 VS 网球运动员……Jessica阐述了自己关于“身份认同”的心理变化,这是一篇“将潜在困难转变为积极因素”的典型大学Essay,面对生活中的“what if假设”,从起初的懊恼,到后面的转变心态,用“重新发现”来积极应对。

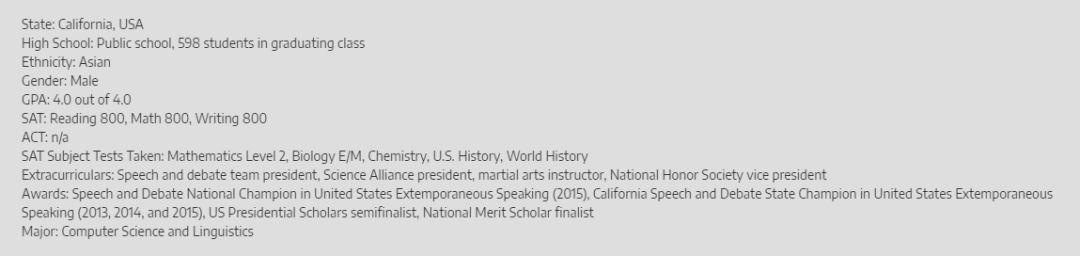

03

亚裔Phillip

ESSAY正文

The summer after my freshman year, I found myself in an old classroom holding a blue dry erase-marker, realizing what should have been obvious: I had no idea how to be a teacher. As an active speech and debate competitor, I was chosen as a volunteer instructor for an elementary public speaking camp hosted by my high school. For the first time, I would have the opportunity to experience the classroom from the other side of the teacher’s desk. My responsibility was simple: in two weeks, take sixteen fifth graders and turn them into confident, persuasive speakers.

I walked into class the first morning, enthusiastically looking forward to the opportunity to share my knowledge, experiences, and stories. I was hoping for motivated kids, eager to learn, attentive to my every word.

I was on the other side of the teacher’s desk, but I hadn’t stopped learning. Each day, I was learning how to communicate more effectively, how to deal with new challenges and circumstances, and how to be a better teacher. I once thought that being an adult meant knowing all the answers. But in reality, adults, even teachers, constantly have more to learn. I made the transition away from being a child during those weeks, but I did not and would not transition away from being a learner.

When class ended each afternoon, I would cap my blue dry-erase marker, give high-fives to the students as they walked out the door, and watch as their parents picked them up. I was confident that when my students were asked the inevitable questions of “Did you learn something today?” and “Did you have fun?” their answers would be a resounding yes. And even as their teacher, I learned and had fun too.

Instead, I got Spencer, who thought class was a good time to train his basketball skills by tossing crumpled speeches into the trash can from afar. I got Monica, who refused to speak, and I got James, who didn’t understand the difference between “voice projection” and “screaming.” I got London, who enjoyed doodling on her desk with permanent marker, and I got Arnav, who thought I wouldn’t notice him playing Angry Birds all day. The only questions I got were “When’s lunch break?” and “Why are you giving us homework?” and the only time I got my students to raise their hands was when I asked “How many of you are only here because your parents forced you to?”

Just ten minutes into class, two things hit me: Spencer’s crumpled paper ball, and the realization that teaching was hard.

When I was younger, I thought that a good teacher was one that gave high-fives after class. Later, of course, I knew it was far more complicated than that. I thought about teachers I admired and their memorable qualities. They were knowledgeable, enthusiastic, and inspiring. Their classes were always fun, and they always taught me something.

There was plenty I wanted to teach, from metaphors to logical fallacies. But most importantly, I wanted my students to enjoy public speaking, to love giving speeches as much as I did. And that’s when I realized the most important quality of my favorite teachers: passion. They loved their subject and passed that love on to their students. While it wouldn’t be easy, I wanted to do the same.

Every day for two weeks, I searched for creative ways to inspire and teach my students. I helped London speak on her love for art; I had Arnav debate about cell phone policies in schools. And by the end of the camp, I realized that my sixteen students all saw me not as a high school student, but as a teacher. I took their questions, shared my enthusiasm, and by the time camp was over, they weren’t just learning, but enjoying learning.

点评:这篇essay主题是经过慎重考虑的:作者没有用华丽的功绩让我们眼花缭乱,也没想着炫耀取得成就的广度和深度。相反,选择了一个简单的小故事,依靠在公共演讲训练营与孩子们一起工作的经历,突显个人成长。此外,Phillip的文章自信且清晰,他是在讲故事,而不是炫耀吹牛。

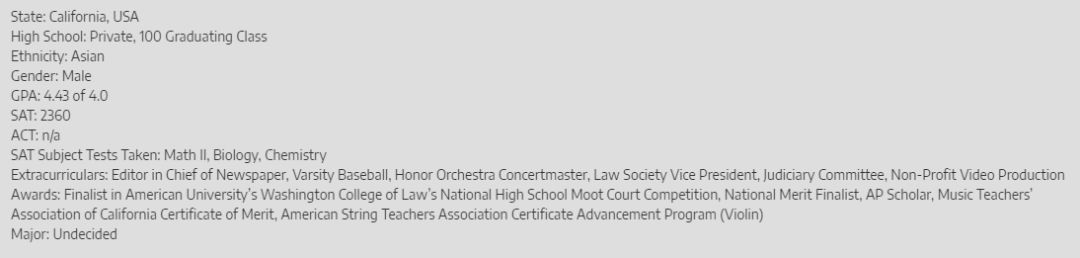

04

亚裔Chad

ESSAY正文

The man was a prodigy. He had performed for American presidents and even the Queen of England, every moment documented with autographed photos hanging in his guest bathroom. Even with a stature of 5 feet and change, his presence towered above me unforgivingly. His skeptical eye stared down at me as I struggled to balance my mom’s iPhone on its makeshift tripod. A month earlier, the Pasadena Symphony-Pops had commissioned me to create a video featuring its debuting conductor, Michael Feinstein.

Now, the five-time Grammy nominee hunkered down on his piano bench, impatiently waiting for my command. With no professional equipment and little preparation beforehand, I had thrown together whatever I could find. A day before, I had taken pliers to bend a coat-hanger into a holder for the purple-cased iPhone 4. I even used a block of Post-Its to prop up a second-hand GoPro for another camera angle. Fumbling about, I felt like a child looking desperately for direction, almost expecting an adult to hand me a checklist—complete with the right questions to ask, directions to give, and instructions to complete. But I was on my own now. My “wing-it” approach to the shoot quickly became obvious, and Feinstein’s skeptical reception grew into condescension as I stumbled painfully through the interview. The filming ended, and heavy doors swung shut behind the mansion as I was escorted out.

I had blown it. Academic rubrics and guidelines were straightforward—but here, being a straight-A student in the classroom held little value. For the first time, the Feinstein project had given me the opportunity to conduct my own show—but I had arrived without a baton. The MacGyver camera rigging wasn’t the flaw; in fact, I think I pulled off the creative contraption decently well considering my lack of better resources. The real failure was my complete lack of preparation and absence of confident leadership. Yes, it would’ve been easy to write off Feinstein as arrogant—he certainly didn’t serve me a generous helping of grace. He had envisioned a director with a camera crew—I was a 16-year-old amateur with my mom’s iPhone. But looking back, I realized that Feinstein had given me a valuable gift: expecting more from me than what I expected from myself. Did I want to just be the teenager with a camera phone? The interview with Feinstein was humiliating, but the experience forced me to decide if I wanted to be that director with his own camera crew.

I took action. As part of the commission, I had already negotiated for the PSA to pay for professional editing software, Final Cut Pro X and Motion 5. I had a vision of what I wanted, but I also had no idea how to use these programs to get there—I was just an amateur with no film experience beyond the occasional school project with iMovie. I dove head-first into editing, determined to not let my inexperience stop me. The process was brutal—I spent countless hours reading online manuals to solve frequent problems. But every frustration fueled determination. Over the course of 80 working hours, the video progressed from a barebones slideshow of images to a multi-faceted film with customized titles and transition animations. The completed production, though far from a masterpiece, gave me a sense of accomplishment knowing that my initial failure propelled me to work beyond my expectations and fulfill my own vision.

I was ready. Stepping back one last time to watch the finished video with my Pasadena Symphony-Pops clients, I no longer felt like the lost boy in the Feinstein mansion. And amidst the excitement and congratulations around me, I wished Michael would have been there too—to thank him for helping me set aside the iPhone and coat hanger, take the baton, and conduct my own show.

05

亚裔Emily

ESSAY正文

Clear, hopeful melodies break the silence of the night.

Playing a crudely fashioned bamboo pipe, in the midst of sullen inmates—this is how I envision my grandfather. Never giving up hope, he played every evening to replace images of bloodshed with memories of loved ones at home. While my grandfather describes the horrors of his experience in a forced labor camp during the Cultural Revolution, I could only grasp at fragments to comprehend the story of his struggle.

I floundered in this gulf of cultural disparity.

As a child, visiting China each summer was a time of happiness, but it was also a time of frustration and alienation. Running up to my grandpa, I racked my brain to recall phrases supposedly ingrained from Saturday morning Chinese classes. Other than my initial greeting of “Ni hao, ye ye!” (“Hello, grandpa”), however, I struggled to form coherent sentences. Unsatisfied, I would scamper away to find his battered bamboo flute, and this time, with my eyes, silently beg him to play.

Although I struggled to communicate clearly through Chinese, in these moments, no words were necessary. I cherished this connection—a relationship built upon flowing melodies rather than broken phrases. After each impromptu concert, he carefully guided my fingers along the smooth, worn body of the flute, clapping after I successfully played my first tentative note. At the time, however, I was unaware of that through sharing music, we created language of emotion, a language that spanned the gulf of cultural differences. Through these lessons, I discovered an inherent inclination toward music and a drive to understand this universal language of expression.

Years later, staring at sheets of music in front of me at the end of a long rehearsal, I saw a jumbled mess of black dots. After playing through “An American Elegy” several times, unable to infuse emotion into its reverent melodies that celebrated the lives lost at Columbine, we—the All-State Band—were stopped yet again by our conductor Dr. Nicholson. He directed us to focus solely on the climax of the piece, the Columbine Alma Mater. He urged us to think of home, to think of hope, to think of what it meant to be American, and to fill the measures with these memories. When we played the song again, this time imbued with recollections of times when hope was necessary, “An American Elegy” became more than notes on a page; it evolved into a tapestry woven from the thread of our life stories.

The night of the concert, in the lyrical harmonies of the climax, I envisioned my grandfather, exhausted after a long day of labor, instilling hope in the hearts of others through his bamboo flute. He played his own “elegy” to celebrate the lives of those who had passed. At home that night, no words were necessary when I played the alma mater for my grandfather through the video call. As I saw him wiping tears, I smiled in relief as I realized through music I could finally express the previously inexpressible. Reminded of warm summer nights, the roles now reversed, I understood the lingual barrier as a blessing in disguise, allowing us to discover our own language.

Music became a bridge, spanning the gulf between my grandfather and me, and it taught me that communication could extend beyond spoken language. Through our relationship, I learned that to understand someone is not only to hear the words that they say, but also to empathize and feel as they do. With this realization, I search for methods of communication not only through spoken interaction, but also through shared experiences, whether they might involve the creation of music, the heat of competition, or simply laughter and joy, to cultivate stronger, more fulfilling relationships. Through this approach, I strive to become a more empathetic friend, student, and granddaughter as finding a common language has become, for me, a challenge—an invitation—to discover deeper connections.

被公布的Powerful essay,没有华丽辞藻,但每篇都做到了一点:“show who you are beyond your resume”——具体来说就是“你的重点是什么,生活中你想要做什么,什么事成就了现在的你,现在你为什么想做这件事“。

因为,招生官知道你上的什么学校,参加过什么俱乐部,经历过什么职业,但是他们不知道这些经历如何影响和造就了你,所以你就是要告诉他们这些,这就是essay的意义。

▼

推荐阅读

重磅!全方位深扒美国计算机专业Top12大牛校

纽约时报:2018年美国大学申请essay精选!

【美国留学中心】最齐全的美国留学资讯,最扯的美国新闻吐槽,最有用的留学攻略,为留学生和即将的留学生答疑解惑。

微信ID:usagogogo

投稿地址:2533137309@qq.com